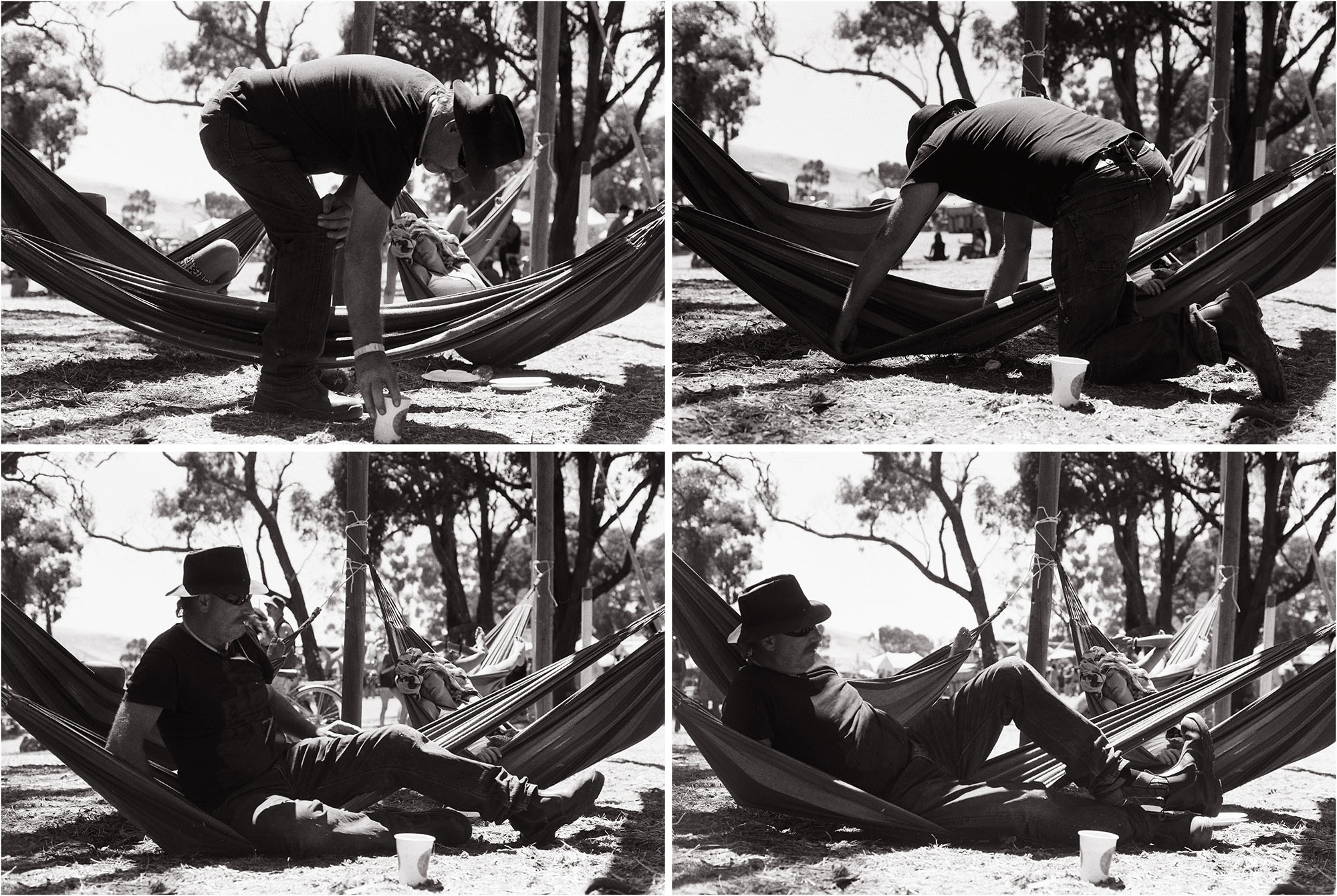

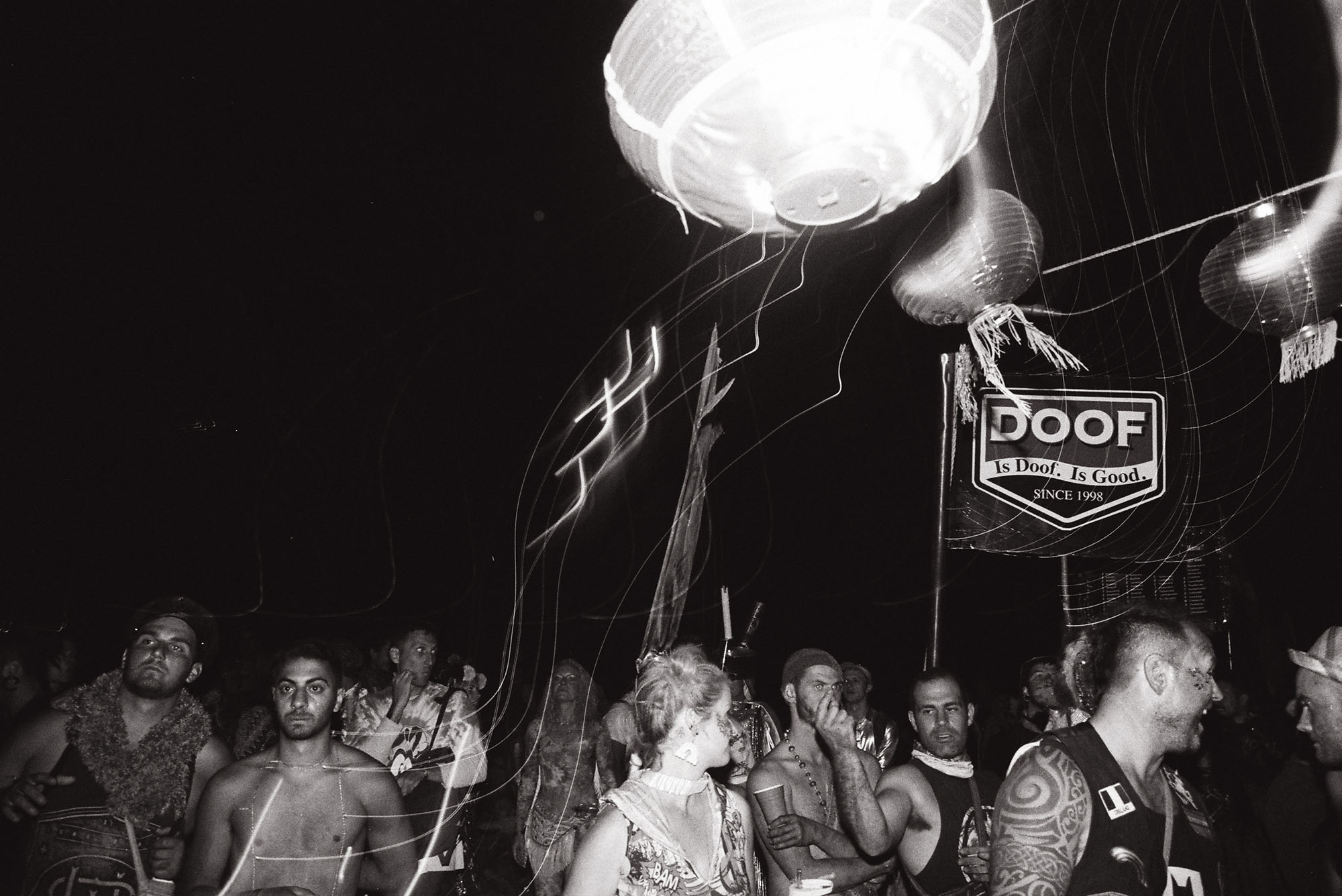

Tis a mad, bad, crazy festival two hours north-west of Melbourne. Hauled with me load of medium format gear and toiled and sweated around the baking stages with it only for them to turn out blank 🙁 so these images are what I was able to capture on 35mm black and white. You win some you lose some. Que sera. There’s always next year, maybe with a dash of colour next time 😉 so here’s the precious cargo of images that did turn out.

Rainbow Serpent 2017

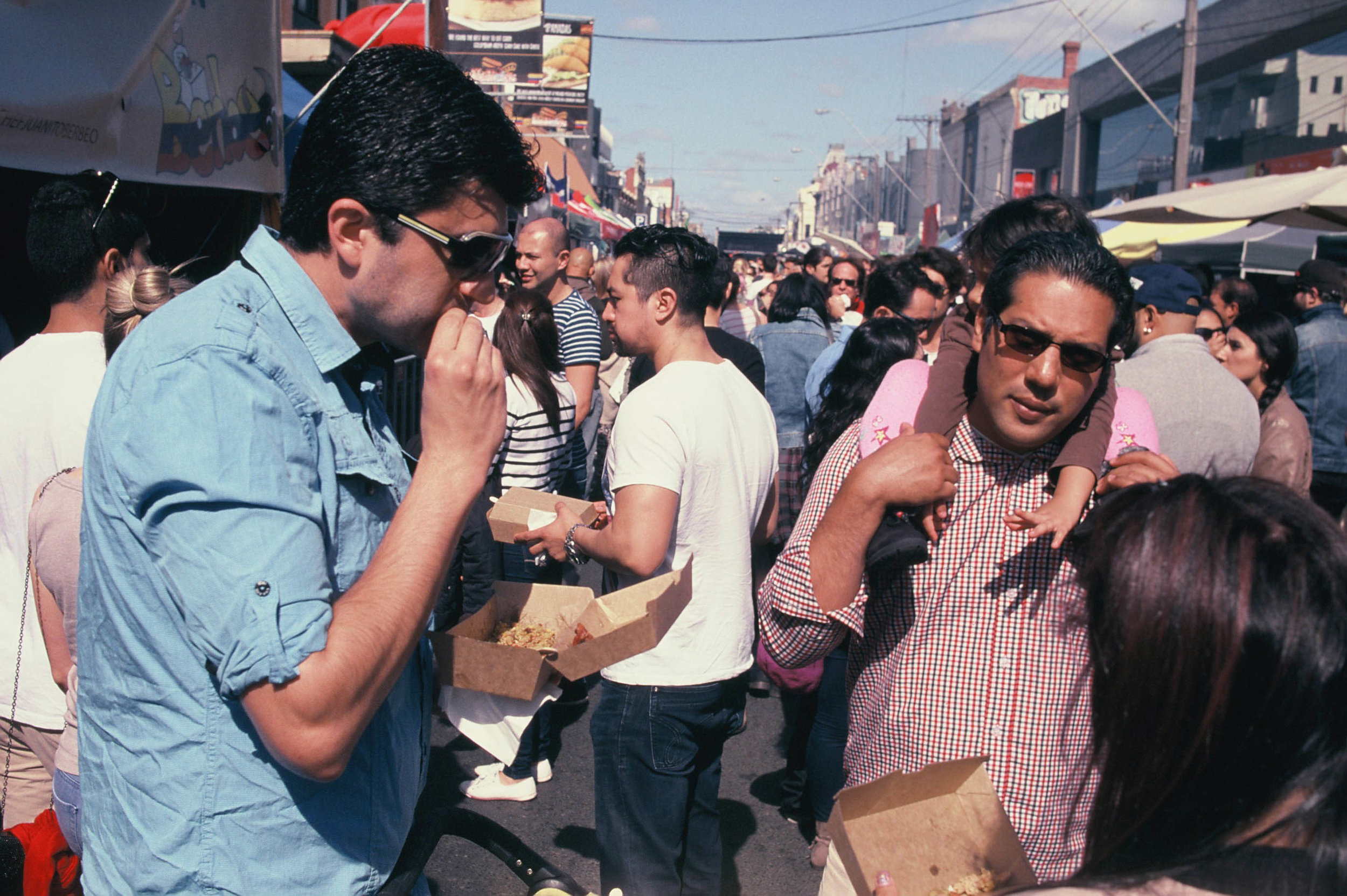

Colombian Street Festival, Melbourne

Here's some film that's been languishing on my desk for about a year undeveloped. Definitely feeling the 24mm lens for tight, busy situations without it giving too much distortion; might be coming to festivals that one!

New Year Feathertop

in Hiking

These are some photos from the New Year's hike we did up Mount Feathertop in the Alpine National Park in Victoria. We got some really mixed weather which mixed things up a bit, two days of hiking in the rain with soggyness all the way through and then a painful climb in 32°C up the Diamantina Spur.

We parked up at Harrietville and headed down a pretty overgrown, lesser used track called the Bon Accord Spur and then had the fun and games of attempting to put up a tent in torrential rain. We woke up to thick fog blowing in and headed up to Mount Hotham where morale (mine at least) was a bit low. No photos and lots of hangryness. Getting out onto Machinery Spur the weather cleared and I could get the camera out again which cheered things up and we descended to Blair's Hut at the riverbed. In the morning we headed up the punishing Diamantina Spur to the Federation Hut campsite and it was beautiful and calm for the rest of the hike. Sunsets and sunrises shot are the last day of 2016 and the first day of 2017.

I managed to keep all the film dry too, all shot on some Sensia 100 that I was worried had been a bit cooked as I left it in my west facing hot bedroom but everything came out. Really pleased with the fine grain and the slightly 70's yellow tinge everything has. Much easier carrying the FM3A instead of lugged a 5D around.

The Island of Komodo

I'd been wanting to go to Komodo Island for some time and it's actually not too far away from Bali - around halfway between Bali and Timor; an hour by plane or countless buses and boats between the inconvenient Indonesian archipelago’s islands.

To get there you need to go through the gateway town of Labuan Bajo on Flores island. It’s kind of like a 1950s Bali. Things are going to ramp up tourism wise because they have a brand new airport that can handle 1.5m passengers compares to 150k before. But for now is dusty and sweaty - air-con isn’t much of a thing so you just have to be happy in sweat. Still, before long I was heading off on a boat around Komodo Island for 5 days to dive with all manner of sea dwellers.

Komodo itself is also one of the most beautiful places I have visited, it feels completely untouched for now - just trees, grass, sand and sea.

Brutal London

My last trip to London - had a little time to wander so I thought I'd explore some the Sixties brutalist architecture around Barbican. There's a kind of weathered dystopian feel to the whole area.

Early in the morning chai sellers fire up their stone burners with coal sending plumes of smoke into the street.

Varanasi's yin, Bodhgaya's yang

Ominous fog has come to rest over the city during the night. I am leaving Varanasi's yin and yang mix of calming ghats and holy mess of crammed labyrinthine streets for some more peaceful climes. Standing in the crowded entrance hall of Patna Junction station and the man at the enquiry desk has just confirmed to me there are no trains south because of the fog so I plod back out to the murky street to look for alternatives.

Just standing at street level in India is a deafening experience. Lorries, rickshaws and motorcycles clatter past you, all loose metal and persistent wailing horns stinging your ears. Bovines and canines alike lie down to doze among tyres and wing-mirrors that skim their fur as they pass by. You can in fact, within reason, walk straight out into oncoming traffic and it simply flows around you like water. In the periphery of the traffic's roar people have themselves shaven, their clothes mended and shoes polished. They eat samosas and pakoras, drink chai and chew paan and excrete all of this into the very same gutter. This cocktail offers a fluctuating aroma of spices, urine, incense and fumes depending on the direction of your nostrils at a given moment.

This is street life, the very same form of life that existed in Western cities and which has since been sterilised into polished concrete high-streets or engulfed by the business of the great malls. Part of the 'magic' of India is of course that this kind of world still exists and why tourists come to be caught up in the cacophony. India delivers the intense multi-sensory stimulation that some people crave when living in comparatively sober cities, myself included. However, there are negative aspects to all this 'stimulation', namely that many of the cities are swimming in rubbish.

So where are all the rubbish men I naively ask to myself. I am curious as to where much of the money comes from (or doesn't come from) to keep the infrastructure of large Indian cities running. After some reading I discover that only 2.9% of Indians pay tax. Indians are only required to pay tax if they earn over Rs-200,000 per year which the vast majority of Indians do not. The average annual salary in India is Rs-20,000 or USD-$295. Of those who can afford to pay tax around 80% of this workforce is classified as 'informal', i.e. they work for themselves and do not file tax returns. Of the 14,800 millionaires in India, most of these exploit the myriad loopholes in the convoluted tax system to avoid paying tax much like millionaires in other parts of the world. Thus, those that do pay tax tend to be those who work for large companies and have the tax deducted automatically from their salaries. The total tax revenue for India then is around Rs-30.3 trillion (USD-$450 billion) which is roughly the same as the total tax revenue for Australia, a country with a population 54 times smaller. There is precious little cash to pay for the infrastructure needed to clean up the cities. Recycling plants have been built around some cities, Kolkata for example, but there isn't the infrastructure to collect the rubbish from around the city nor the tax revenue to pay for the electricity to power them so many are operating at nowhere near capacity. For those to whom the streets are home or a workplace, picking their way through the rubbish for now is the only option.

People watching amidst the ordered chaos I notice the unique personalities attached to each hawker of travel. The quietest and most methodical humans are the cycle rickshaw drivers. They pedal rhythmically around the city waiting to be accosted for service. Any reasonable sum on payment seems acceptable and they are very grateful, touching their heads and hearts with the money and bowing graciously in thanks.

The auto-rickshaw drivers are born of an utterly different skin. Native hustlers, before every journey an agreed destination and price must be hammered out. Passengers are then swerved against traffic from all directions to reach their destination. And the destination does invariably arrive given the unspoken but fully understood laws of the road: the bigger your chariot the greater your powers of parting the sea.

The bus drivers work as a team to a similar effect to the rickshaw drivers but with distinct personalities and roles within the unit. Given the fog's disabling effect on the trains it is by bus that I am making my way south from Patna, one of the oldest cities in the world though you wouldn't guess it from the stacks of white painted concrete apartments carpeting the city, on my way to Buddhism's holy city of Bodhgaya.

My bus has a team of three: the nucleus is a stoic and hyper-alert driver who swings his weight around the steering wheel careening several tonnes of steel through the clogged streets and a conductor in possession of a powerful set of lungs who yells 'Gaya!' the second we come into earshot of likely customers. There is a third assistant who appears to flit around the bus as it stops and starts like a loose electron wrapping his knuckles on the side of the bus whenever the driver has to thread the vehicle through a particularly tight gap - a kind of human parking sensor. As soon I am ushered onboard an episode of shouting and spitting of Hindi between the driver and the conductor erupts. It appears something has been lost as there is much frantic searching around the bus and presumed accusations being thrown. There is a point at which our driver seems genuinely offended and angrily shakes a pointed finger back at the conductor. An elderly passenger caught in the crossfire eventually waves his hand as a signal for the two to finalise their squabble and get the bus moving. We shuffle our way, twisted bumper to twisted bumper, out of the acre of mud that is the main bus terminal. Looking down through the grubby bus window I can hear and see shrieks and animated gestures from other bus conductors as they hook Indians tiptoeing on bricks through the terminal's chocolatey sludge up and onto their buses.

Not long into our journey our harried driver attempts to undertake a bus parked in the centre of the road narrowly missing a man stepping down from the bus with his son. The bus judders to a halt and belongings are flung forwards. More rapid-fire Hindi is blasted between the driver and the affronted man. The aggression seems wholly unnecessary but I assume is the result of an antagonised lifetime spent cutting up and being cut up on Indian roads. Shouts of 'challo' ('let's go') from the back of the bus leave the business between our driver and the man in the street unfinished.

Minutes later we run into a rickshaw driver flouting the law of size by blocking a narrow stretch of country road, refusing to submit to the bus. This is too much for the conductor and the driver who both explode into another installment of yelling and flailing. Arms gesture furiously and a seemingly unsavoury flavour of Hindi is showered down onto the rickshaw driver. Still there is no movement so the conductor springs down from the bus to explain in more detailed terms the essence of unofficial Indian road traffic law. There is cupping of necks and butting of heads and neither is willing to move. Instead we edge precariously through the ditch at the side of the road, the third assistant on the bus gathers up the seething conductor who is still fervently gesticulating and we continue on our way.

After four sub-comfortable hours at the front of the bus on top of the gearbox, surrounded by my bags and with my ample legs stowed somewhere up near my ears we arrive in Bodhgaya. I vow not to take another bus in India unless I absolutely have to. A very senior Tibetan monk is visiting Bodhgaya and the main Mahabodhi Temple Complex is filled with Tibetan Buddhist monks who are spending several months here while the cold winter takes hold in Tibet. I make my way with them through the Temple Complex to the Bodhi Tree that flanks the Mahabodhi Temple. I sit at the back and a monk near me kindly offers me a cushion. After the aggression of the journey south I am now able to shut my eyes and sit peacefully among the gently chanting monks for the next two hours. Such is the energy here that my mind doesn't wander and I am able to soak up the calm with minimal concentration. It feels to my mind like applying moisturiser to incredibly dry skin does or shampoo to your hair when it's really dirty.

It's is certainly not an easy task but it is possible to find some peace in India and this invariably involves finding a sacred place. Even then, despite the fact that many of the streets are too narrow to fit anything larger than a motorcycle down, Varanasi is far from a tranquil haven and more of a thumping celebration of Hindu culture. Thankfully most of the temples in Bodhgaya lie away from the hum of the streets so this is a perfect place to spend some time before re-entering the the clamour in Kolkata.

A passenger adjusts his scarf to protect himself against the Indian winter chill while other passengers disembark with sacks of belongings.

Monsoon wi-fi

I'm in a small village in Uttar Pradesh and I'm trying to make a Skype call to Ma and Pa to send some festive cheer. Unfortunately the place that I'm staying in is bereft of internet access because of 'unpaid bill' if I'm to believe the message I'm presented on login. I've found a restaurant that has wi-fi and agree to Skype with my parents at 6pm but on my return the owner says to me 'wifi not working' so I ask around at a few other places and it is clear that wifi is temporarily defunct for the entire village. I feel like I'm coming down with a cold because I naively didn't bring very many warm clothes. I'm leaving tomorrow on a 3 hour train journey to a town called Chitrakut so I figure I'll get some rest and try again tomorrow as there's nothing more I can do here.

Sure enough, I wake up feeling like I've been hit by a freight train, check out of the hotel and shiver my way on a 40 minute rickshaw jaunt to the village train station at 6am, not helping my cold. There's a shopkeeper selling steaming hot chai tea so I buy one and huddle around the small stone hearth outside his stall to warm my hands. He adds a couple of extra fuel bricks to stoke the fire made from dried buffalo dung cakes called 'gomaya'. There's no-one at the station save for a couple of cows nosing through the bins for scarce signs of nutrition.

The train arrives on time and I'm on my way although with all the windows and doors open there's a cold blast whistling through the compartment. I wrap myself in the scarf and thin blanket that I have and watch the wheat fields, cows and rocky outcrops pass by. The train starts to fill up with locals bringing many different goods: wraps of sticks, sacks of potatoes, bicycles. It becomes increasingly difficult to establish which station I'm at; some of the stations have names in English, some only in Hindi, some not at all. The train gets delayed at a country station. There are no announcements so I get out and take a look and all I can see is a red signal. There are lots of goods trains passing through carrying coal and I hypothesise that we must wait for the lines ahead to be free to satisfy my own personal need for an explanation. We all wait patiently at this station with no crying from children or grumbling from adults. 2 hours pass and the train begins to creep forward once again. As we roll forwards I crane my head to see past the accumulating crowds and ask my fellow passengers for station names. I receive a mix of responses and try to assimilate the information to establish my location.

Despite the neck-craning and enquiries I miss my station. As I am on the Allahabad train it looks like this is where I will be staying tonight. I ask the man now sitting opposite to me where he is going and he replies 'Allahabad' so I will just get off when he does. We have a second unexplained 2 hour wait at another lonesome country station. My stomach rumbles but I'm worried the array of luke-warm salads and puri carried on the heads of the elegantly grubby and enervated sari-clad women will move the movements of my feeble Western bowels into territory I'd rather not explore on this crowded convoy. The train's latrine is not a place to unwind with an iPad and make social media updates. I take a few handfuls of the trail mix I have in my bag to pacify the most immediate pangs of hunger.

The dusk gives way to night and glittering acid yellow lights begin to stipple the horizon. We trundle through the fog into a large station station and the man opposite me takes his belongings and alights with me in his wake. The delays at the country stations have protracted the usual Orchha to Allahabad journey from 6 hours to 14 hours. I plod out of the station drained and thick-headed from my cold with with my travelling appurtenances weighing me down. I make my way apparently north having had plenty of time to study the Allahabad map in my well-thumbed loaned Lonely Planet guide. I've picked a hotel close to the cathedral and ask for directions. After numerous rotations of the map and blank looks I learn that the man opposite me didn't disembark in Allahabad but in Naini, a satellite town to the south. It's getting late and there is a paucity of rickshaw drivers but I find a driver willing to take me to the hotel I'd chosen in Allahabad. It's not too far and we agree 200 rupees. We putter across the 1.5km Yamuna Bridge, one of the longest in India, close to the Triveni Sangam where the muddy Ganges and the deeper clearer waters of the Yamuna river meet. This is site of the Kumbh Mela where every 12 years around 120 million Hindus gather to bathe in the river. We pull up by the roadside and my driver turns to me.

'Here is hotel'

I look up at the sign on the front of the building which reads Hotel Aurangzeb.

'This isn't the hotel I asked for'

'Yes, this is hotel'

'Can you take me to the Hotel Tepso please'

'This is near district city lines, very far from here, another 200 rupees'

'We agreed 200 rupees to Hotel Tepso'

'We agree 300 rupees'

I'm tired and cold, my body aches and all I want is sleep. Our exchange escalates to a heated debate and it seems our prior agreement in Naini has been lost in the winds crossing the Yamuna Bridge. I dig my heels in and refuse to pay until we arrive at Hotel Tepso. My driver castigates me for not playing his game of 'ring-a-ring-of-commission-paying hotels', grudgingly rotates the rickshaw and acquiesces to drive me a further 2 minutes to the agreed destination to receive his 200 rupee payment.

The Hotel Tepso is a little more expensive than my accommodations to date but given my state I gladly pay the 1,500 rupee charge and collapse into my room. The man at reception comes to my room to show me the convoluted operation of levers and switches I must engage to ensure myself of a hot shower in the morning. I request the wifi password while he is here and key it into my laptop. 'Invalid password' is the response. 'No, password is right, computer is wrong'. I have little to no life left in me to have this discussion and instead make a quick search on his computer at reception to see how I go about unearthing his wifi password. After a 15 minute rummage through the internet it turns out this is not an easy task on tools of the Windows 95 era of personal computing for those with sub-network administrator skills. I abandon the exercise and resolve to find another hotel in the morning after some essential recovery.

After a long rest and my first hot shower in India I haul myself through the dusty streets of Allahabad to seek out another hotel. I find a room at the large and rambling Hotel Prayag where the wifi works. With my Westerner's thirst for internet slaked, I fire off some emails and plan to rest here for a day or two. I'm going to need to recoup some strength before I head to the bustle of Varanasi next week.

Before flying to India

India is a place I have always wanted to travel to but there was always a different option to travel somewhere else and the time was never right.

Tomorrow I am flying to, by some estimates, one of the fastest growing cities in Asia; Delhi. I am fascinated to explore some of the intense development that has been occurring here in the last decade with a plan to then move east and learn about some of the regions that have fuelled this development in the industrial towns of Dhanbad and Bokaro. On the way I will hopefully encounter the holy city of Varanasi and the great Taj Mahal and stay respectful and sensitive. Sometimes that card be hard given the violence of photography but as long as respect is forefront in your mind I think it can be done.

This is the first real trip that I have done that is entirely about photography so all that's left is for me to get into that meditative state and wander the Indian streets.

The Resting Trees

Stormy Woolamai Surf Days

Last month we headed down to Philip Island for a surf and were woken early in the morning by heavy rain and ear piercing cracks of thunder. Making our way out of the city we even saw lightening strike a telegraph pole immediately in front of the car sending sparks scattering across the glassy surface of the road. Two hours of driving later we arrived at a pond-like Smiths Beach with the rain still falling. With the waves being non-existent we decided to take a look at the notorious Woolamai. Woolamai Beach usually presents the challenge of 6-foot plus waves and strong rip currents but for this occasion they were just about surfable for me and my rudimentary skills so we donned suits and headed in.

Sitting out the back and waiting with around 8 or 9 surfers there's a unique sense of solidarity you can feel with everyone around you. There is no talking, just concentration on the waves and the even pattering of raindrops on the surface of the sea. It fascinates me how connected you can feel despite not talking or even looking at your fellow surfers.

It is a beautiful thing.

Taking over The Mayfield in Richmond with Chris and Gus

Further developments...

I ended up getting myself into a minor funk last week by feeling a little swamped with all of the strands of my current street photography project based in Melbourne. I'd been exploring a number of different avenues but for some reason I was struggling to weave all these ideas together into a coherent story so I broke everything down and shared these strands with my friends Chris and Gus.

Turns out there's really multiple projects here and the adage 'keep it simple stupid' doesn't ring truer. So much so that I dusted off the medium format gear and have spent this week re-shooting some key scenes, slowing down and focusing on the things that have worked so far.

I'm looking forward to getting the first few rolls dunked on Friday so I'll put up a post to share that experience.

Stephen Dupont discusses sequencing at the Biennale workshop

7 Things I Learned From My Portfolio Review

This weekend I went to the small city of Ballarat in Australia for the Ballarat International Foto Biennale. I took a portfolio of prints of my most recent project with me in the hope I would get some nudges in the right direction. I also took part in a one-day workshop led by the very experienced and inspirational Stephen Dupont. While it’s still fresh in my mind, here is what I learned from the experience.

1. Learn to embrace the deflated feeling you get from being criticised

Of course it’s constructive criticism but it's not going to make you feel good like gushing praise will. But gushing praise isn’t going to make you better at what you do. Constructive criticism will. You’re going to feel a bit deflated that your project isn’t where you want it to be but that deflated feeling is the feeling of the gap between your reality and imagination getting smaller. Drink it in and apply it. Here’s Ira Glass talking about that gap.

2. Be specific in your project - don’t bite off more than you can chew

Find one thing that you are really doing well in your project and nail that. If you have even a tiny doubt about an image then lose it. It’s not good enough. I learned the painful way this weekend and I should have known better. Have the balls to look at what might be a great image and leave it out of a story if it doesn’t fit.

3. Don’t recreate other people’s work - be you

Looking at other people's work is great, especially the masters, and there is much to learn from it. But make sure your work is coming from within you. Those people have made that work from within them and that's theirs, now you make yours.

4. Study aesthetics

Pore over your images and pay close attention to the tiniest details. Even details you think people won’t notice. Especially those details. Read up on the classics of aesthetics and think about how people are going to be drawn into your image. Alasdair Foster pointed me in the direction of Vilayanur Ramachandran. Here’s a lecture of his on Aesthetic Universals.

5. Learn to step outside of your own mind

This is a real skill. You know all those thoughts and emotions you had when you took that photo? Your viewer won’t have any of them. Learn to ‘cold read’ your images to try and put yourself in your viewers shoes and feel what they are going to take directly from your image.

6. Collect EVERYTHING

In a world that is now completely saturated with images on Facebook, Instagram and elsewhere on the web, and where everyone is now a photographer, the question is how do your elevate yourself as a serious photographer? Stephen Dupont’s photobooks really demonstrate and reinforce the notion that the process of photography is an art. His images combine diary snippets, silk prints from India, notes from participants and many other found objects from his travels. It is these things that build a full story, add depth to his work, provide inspiration on their presentation and elevate them above even some of the best news photography, let alone the ocean of other images on the web today. So collect everything on your travels - it might go into your work it might not - but it is definitely going to add depth and point you in new directions.

7. Think of the first image in your story like the first page of a book

I already new that to start a story you need to hit your viewers with a great photo, but think of it like a story book - you wouldn’t tell the reader the main plot twist at the start. So, it might actually not be your best photo but it needs to pique the curiosity of your viewer, hold their attention and make them want to see what comes next. If your best shot sums up the whole story in one shot that’s amazing, you nailed it! But it’s probably not the best photo to start with because they already know what happens in the story.

I hope if you read this you found it useful. I definitely recommend working towards a portfolio review, sharing your work, listening to the feedback and using that to push your inspiration to levels you didn’t think you had before. And I hope this is useful to someone out there.

LINK - Reddit post

Portfolio project #1

After 6 months of work on this project everything is now printed and ready to go. It’s been really exciting, during the final stages, watching my work come together into a physical form. During the midst of a project it is difficult to envision how it will turn out except for in my imagination. That’s what I feel you have to hold on to with all your energy if you have any hope of making it to the end.

This project is by no means finished – I see this as something of a living work as long as I am based here in Melbourne. It has definitely spurred me on to think about deeper long term projects and I’m excited to get some feedback at the Ballarat Foto Biennale.

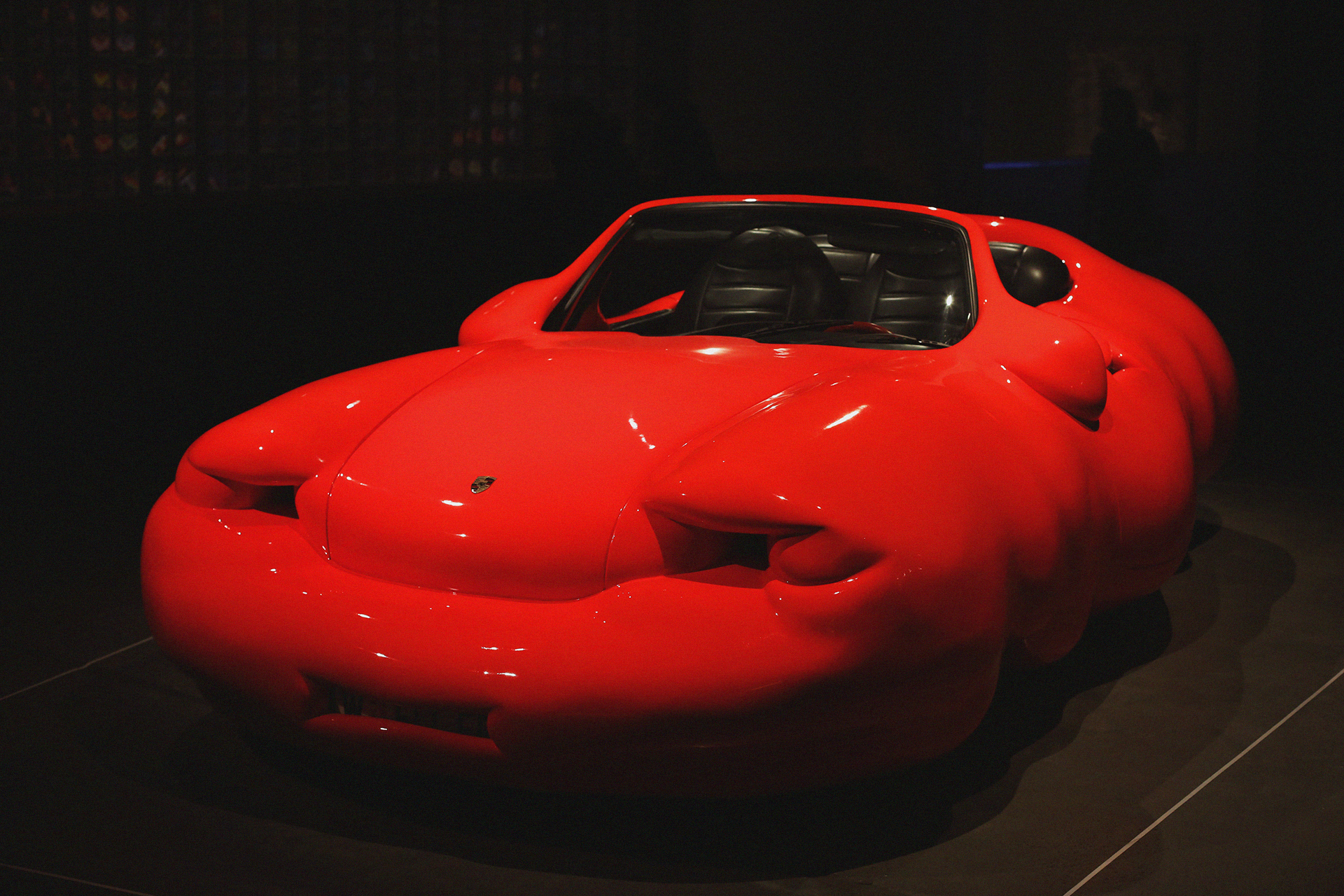

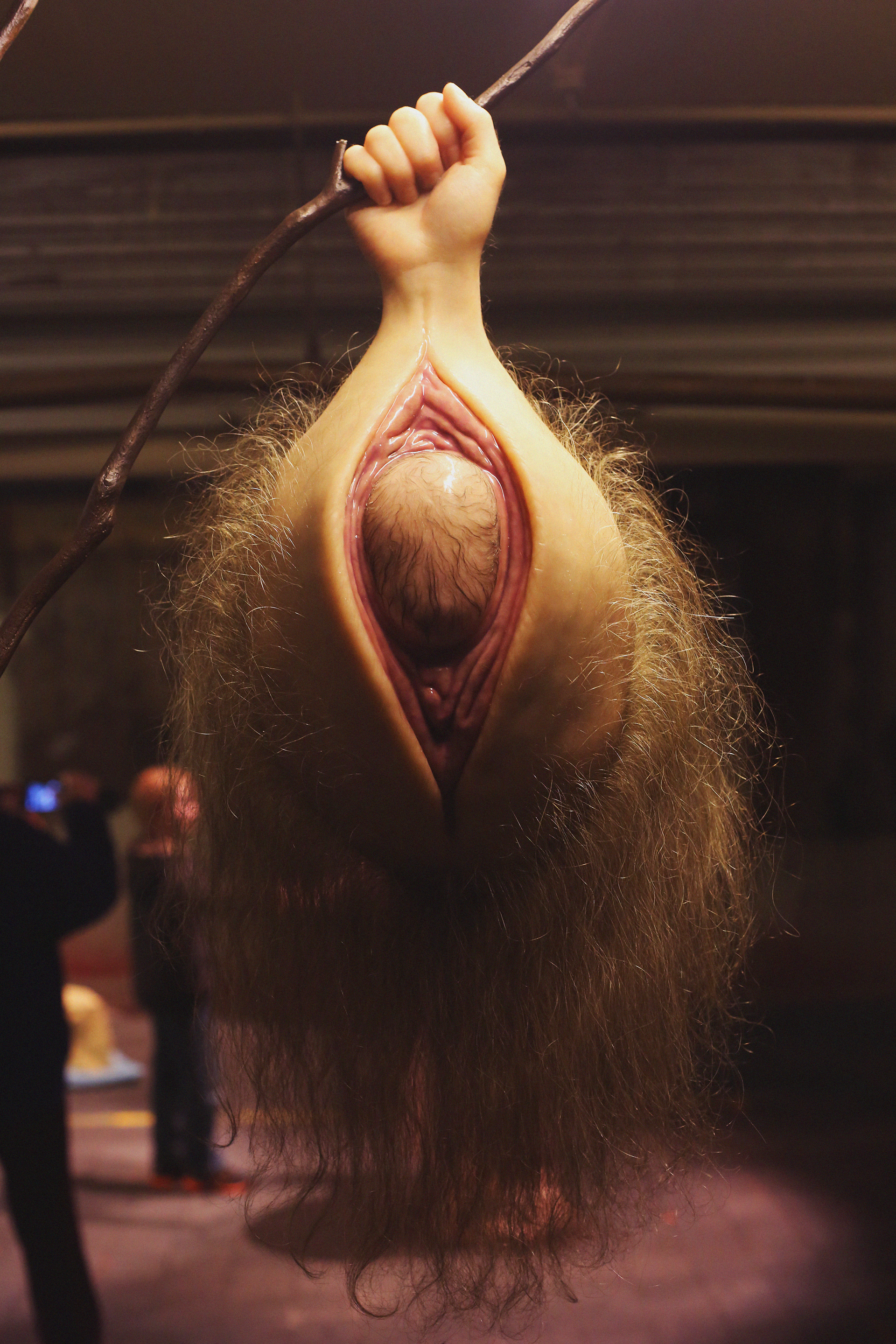

The Art of Dark Mofo

5 days in Tasmania means spending a day at MONA - Museum of Old and New Art. MONA is a privately funded museum by David Walsh who made his millions in the gambling industry and has since become a bit of a hero in Tasmania for tourism he brings in because of MONA.

A lot of the art we saw appealed to the senses as you would expect from an art festival. Marina Abramovich's work was very puzzling - rooms where you can 'feel the energy' from different crystals and counting individual grains of rice.

The images of the grotesque 'creatures' was a fascinating piece where the artist had responded to the cellar-like exhibition space by imaging creatures that could have evolved in this place without outside contact. Doing this meant you really felt like you were experiencing another world in it's own environment rather than looking at objects in a gallery setting - definitely one of the highlights.

It was also great to see some of Tessa Farmer's work in the flesh - this is the hedgehog covered in tiny fairies. The scale of the tiny fairies is unbelievable and they are apparently anatomically correct too. You may have seen her work on Amon Tobin's ISAM album artwork.

Erwin Wurm's 'Fat Convertible' is also a satisfying comment on our modern day excesses.

Here's some images of the pieces we saw while at Dark Mofo.

Hugo Boss Launch Event

Staff occupy themselves in a flurry of cleaning prior to the event launch while others make final arrangements.

Buy more chips...

This image was inspired by an essay I read by Nestor Garcia Canclini where he argues that public space now overflows the sphere of classical political interactions ... and it's this space which is driven by consumerism.

This ad for McDonald's was eye-catchingly direct and generic at the same time.